Remarks delivered by Catherine Clinton, Queen’s University Belfast, at the Southern Historical Association annual meeting, Nov. 2, 2013

Let us pause for a few minutes to remember the life of our dear friend CAROL BLESER

(1933-2013). Those of us gathered together here recognize just how important scholarly & teaching communities can be.

Carol was a fierce mentor and partisan in the tumultuous decades of her academic career. She always advised younger members in our profession to volunteer, to value above all loyalty and friendship–put your heads together young and old, block vote to outmaneuver and don’t forget to appreciate those who undertake thankless tasks that make our profession a collegial place.

Carol was an indomitable force within the field, from her early days at Converse College to her Columbia University years as a graduate student, earning a doctorate in American history in 1966…..at the age of 32.

Carol was an indomitable force within the field, from her early days at Converse College to her Columbia University years as a graduate student, earning a doctorate in American history in 1966…..at the age of 32.

And I must acknowledge the ways in which my complaints in the late ’70s about gender bias–which I described in a New York Times editorial about the Ivy League in 1980 as “Women’s Graves of Academe”–my diatribe seemed pathetic wingeing by comparison with that endured by pioneers who cracked the glass ceilings, courageous women like Carol who prodded and pushed their way into all-male councils–not to seek a solo role, but to share the wealth of their information about breaking down barriers and making headway during increasingly challenging times.

Going first might not always be a symbol of being ladylike, as it meant asserting oneself as Carol did with her Ivy League degree–with her Woodrow Wilson fellowship, with her role in the National Historical Publication and Records Commission, then on to her teaching at Colgate University from 1970 to 1985 with a return to South Carolina as the Kathyrn and Calhoun Lemon distinguished chair in history at Clemson University.

Her contributions to southern history were prolific–with her 1981 volume The Hammonds of Redcliffe reaching a wide trade audience, and the volume for which she may be most remembered, Secret and Sacred: the Diaries of James Henry Hammond in 1988. They exemplify her ability to shape edited documents into compelling southern storytelling, a gift which she shared with her heroic undertaking to launch and maintain the Women’s Diaries and Letters of the South publication series.

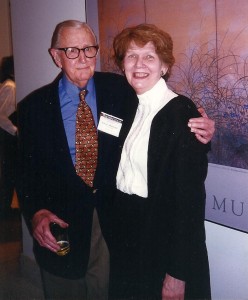

In the year 2000 she retired from her teaching post in South Carolina, & returned to her  home in Bellport, Long Island, where her husband, Edward BLESER, a nuclear particle physicist, had a distinguished career at the Brookhaven national laboratory. Ed was a frequent visitor to the SHA conferences & a passionate preservationist, as was Carol. Both of them gave selflessly to the Bellport historical commission (which Ed had founded) and the Bellport Bellhaven historical Society (with Carol serving as its President) until Ed’s untimely death in 2010. They had a marriage and partnership that spanned more than forty years.

home in Bellport, Long Island, where her husband, Edward BLESER, a nuclear particle physicist, had a distinguished career at the Brookhaven national laboratory. Ed was a frequent visitor to the SHA conferences & a passionate preservationist, as was Carol. Both of them gave selflessly to the Bellport historical commission (which Ed had founded) and the Bellport Bellhaven historical Society (with Carol serving as its President) until Ed’s untimely death in 2010. They had a marriage and partnership that spanned more than forty years.

Carol was an early active member of the SAWH, founded in 1970, and I well remember her propelling me to my first SAWH caucus–as she was instrumental in involving younger women–indeed that’s where her steel magnolia  credentials may have blossomed. She provided the yeast which helped the organization to grow, serving as president in 1980.

credentials may have blossomed. She provided the yeast which helped the organization to grow, serving as president in 1980.

She was incredibly generous with her fundraising and her own donations, giving time and money to that which she believed was central to our profession. Far from seeing our organization in any way as in the margins, she saw the efforts of this group as central to the transformation of our field–something which I think is undoubtedly demonstrated by the ongoing quality, breadth and depth of contributions by women historians as well as by historians of women, especially by those who are both.

After 30 years of service in the SHA, Carol was elected president in 1998–and did so much for so many to promote the cause of women.

It was deeply distressing to her that ill health did not allow her to travel as often as she wished–especially to her beloved annual Southern meeting.

It was deeply distressing to her that ill health did not allow her to travel as often as she wished–especially to her beloved annual Southern meeting.

During my frequent visits, which increased following her widowhood in 2010, I might put pen to paper on her behalf–she was unable to use her hand properly, to scribble the notes she enjoyed posting as well as receiving. Yet she always wanted to let friends know that she appreciated your calls and eagerly sought news of friends–although she was shy about sharing her own troubles, like her diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in May 2013.

The year of her SHA presidency, Carol shared her presidential reception with long time friend C. Vann Woodward on his birthday.

She died on August 20 at her home on Academy Lane, in her beloved Bellport, New York, & a few days later was buried in Connecticut alongside her husband. I have a number of photographs from her memorial last weekend in New York. I will have them posted on our SAWH website.

This past summer, I knew she did not want to broadcast her situation but I was grateful that the bulletin that our president Rebecca Sharpless conveyed via our electronic list resulted in a cascade of postcards and letters–as she always looked forward to the post. And she was deeply gratified to hear from former colleagues and friends, even if she was not able to respond.

So this community of women historians, historians of women, supporters of women’s history could rally round one of our pathbreaking and stalwart members and find a way to let her know that she was not forgotten. And as George Eliot concluded in Middlemarch: “the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive, for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts.”